Experts Talk: Leveraging Innovation in Infrastructure P3s with Gail Lewis

Experts Talk is an interview series with technical leaders from across our transportation program.

How To Get the Most Value From Public-Private Partnerships in Transportation

The first legislation enabling public-private partnerships for U.S. transportation projects was passed in 1989 by California. Many other states have followed suit, especially since 2010. Notable successes across the U.S. range from Texas Department of Transportation’s Comprehensive Development Agreement program to South Mountain Freeway in Arizona to the I-95/395/495 Express Lane systems in Northern Virginia.

P3 partnerships work well when private sector technology and innovation combine with public sector incentives to deliver much needed infrastructure improvements on time, within budget and with quality at the forefront. As public entities examine and apply this approach, many see more and more situations where it makes sense.

Gail Lewis is a principal consultant in our advisory services group. As a leader on project finance and strategic planning, she observes how and where P3s are developing and shares insights with her clients on project structure, risk and financing. Before joining us, Lewis spent nearly 30 years in Arizona government where she started, developed and led all phases of the successful P3 program for the Arizona Department of Transportation. In this interview she shares how to leverage innovation and get the most value from transportation infrastructure P3s.

Q. Where and when do P3s make sense today?

A. Many of the early U.S. P3 projects were toll roads, and the perception remains that P3s and toll roads are almost synonymous. Those projects have a dedicated long-term revenue stream — toll revenues — which lends itself well to the P3 model. But P3s go far beyond toll roads. Arizona delivered a building via P3. Toronto's Ontario Line subway is a P3. Los Angeles International Airport's new automated people mover is a P3.

Generally P3s work best for big or complex projects, or for bundles of projects such as Pennsylvania’s Rapid Bridge Replacement project which bundled multiple bridges into a single procurement. The broadband and electric vehicle charging projects that are being promoted through the recent infrastructure bill may lend themselves well to innovation in P3s so a number of states, including Arizona, Iowa and Kentucky, are looking into P3 broadband or electric vehicle charging initiatives.

It’s important to be familiar with the definition and laws guiding P3s. Some jurisdictions have a specific definition of P3; legal limits differ state by state, and sometimes even agency by agency within a state. The Federal Highway Administration defines P3s as "long-term contractual agreements between a public agency and a private entity to design, build, finance, operate and maintain an infrastructure project." National organizations, such as the American Road & Transportation Builders Association’s P3 Division, or the Association for the Improvement of American Infrastructure can help with rules in specific locations. In our advisory services practice, we also find a lot of ideas to share across owners that help develop a strategy specific to each project.

Progressive P3s are a new and more nuanced option getting a lot of attention. These use a more stepped approach. The owner chooses a development team largely based on qualifications and collaborates to develop the design and allocate risks in a transparent manner. Typically these move to a fixed price agreement. Progressive P3s add to an agency’s continuum of project delivery options — everything from traditional design-bid-build to the many forms of alternative delivery. These are all approaches designed toward providing the best value.

So the challenge is not to ask “P3 or not?” The challenge is to think about the best value approach to a project. There are times when P3s can help define the project and assign the risks more appropriately, as well as help ensure good performance. That’s the sweet spot.

Q. How should an agency sort through funding and financing strategy decisions?

A. We encourage our clients to start with a Value for Money analysis. It compares, for a given project, the aggregate cost/benefit of a P3 procurement versus a benchmark conventional public procurement. The Federal Highway Administration’s P3 Toolkit has a great primer on this topic.

The VfM is critical to deciding on a project delivery approach. Interpreting the results is where good advisors really prove their worth.

Let’s remember the difference between funding and financing. Funding means you have a revenue source to pay for the project overall; financing is more like the loan that lets you build the project today while paying back the loan with the future revenue stream.

One common funding stream is tolls. Another option is concession agreements, such as where an agency lets a broadband operator build in their right-of-way or lets an electric vehicle charging operator provide EV charging services using public funds. Owners can also use their traditional revenue streams such as taxes or grants.

For financing, some federal loans, such as Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loans, can support alternative delivery with interest rates that rival public bonding. But one thing that normally distinguishes a P3 is that it usually uses upfront private finance or private equity no matter how the financing is repaid. Private finance from a developer can also give an owner leverage in guaranteeing that design and construction are on time and on budget by structuring payments so that developers only get paid when performance goals are met.

Funding and finance opportunities play a major role in determining the best delivery method and the VfM analysis helps an agency structure and coalesce the best approach for each situation. We have a great team that helps public agencies think through this process; it’s a differentiator for us.

Q. What techniques have agencies used successfully to work through project risk analysis when preparing for discussions with P3 teams?

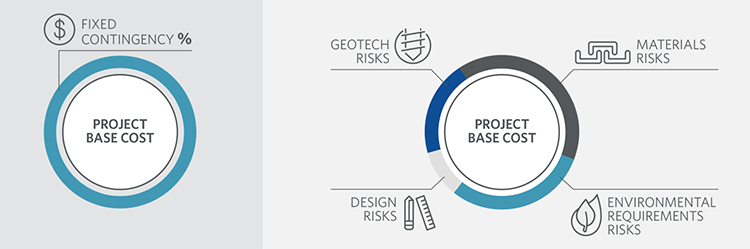

A. We recommend getting everyone on the owner’s side in the room for the risk workshop that’s a keystone for the VfM analysis. The decision support tools we use for a risk workshop are an integral part of the decision-making process. Jose Theiler described these in some detail in a recent Experts Talk on Risk Management. As the graphic below illustrates, rather than handling risk contingency dollars as a single fixed pool, it helps owners when risks are instead broken down at a more granular level. During the risk workshops the owner’s team identifies different types of risks and analyzes them within a quantitative and probabilistic framework.

This type of risk analysis helps explore and quantify different sorts of risk, then helps define and assign risk to the party best able to manage it. Risk considerations will vary from state to state, or even project to project. For example, are utilities a risk that can be taken on by a private partner? If so, and if the parameters can be clearly defined, that is a complex risk that the public sector may be able to hand off. Conversely, contractors who only build the project, but aren’t responsible for long-term maintenance or complex operations, are handing almost all of that long-term maintenance risk back to the public sector.

Owners who explore and analyze risks thoroughly through a risk workshop and VfM analysis can better choose how to allocate and mitigate risk. This further informs the discussion on the optimal project delivery decision.

Q. Where do you see innovative thinking coming into play?

A. The private sector is working on a wide variety of projects around the country and sometimes around the world; that perspective brings fresh ideas to complicated projects. Developers can influence the project early on through alternative technical concepts — options that were not in the scope but that can improve or lessen the cost of the project. ATCs are common in design-build and P3 procurements and a great way for developer-bidders to bring innovative design ideas to the table. Owners can even choose to purchase ATCs from an unsuccessful bidder if they ultimately select a different team.

I worked for the public sector for many years, and it can be a challenging environment to try new approaches, even when it’s obvious that the existing methods aren’t working. Private project delivery partners can bring fresh ideas, so that public agencies don’t need to define new approaches on their own. I always remember that innovation, by definition, is really just something that YOU haven’t thought of yet!

Here’s a great example of a simple solution that a private partner presented to the owner by considering whole-life costs. Because health care is public in Canada, the government has used P3s to build hospitals. For a project in Alberta, the development team shadowed the staff, asking questions and taking notes. One thing they were told was that plastering and repainting walls was a major maintenance problem — gurneys, wheelchairs and mobile equipment were always damaging the walls. So the developer ran the terrazzo from the floor up the walls. It was expensive to install, but it quickly paid for itself in reduced maintenance costs. Innovation doesn’t need to be Einstein-level genius to be significant.

Q. How does the U.S. market compare to that of other countries and what does that teach us?

A. Throughout the developed world, the limits to P3s tend to be more political than practical or financial. Many equate P3s with either privatization or high private profits at the public’s expense. Canada faced these concerns, but the positives have outweighed the negatives, and as more and more projects have been delivered successfully as P3s, they have gained more momentum. Canada also has a federal office and many provincial offices specifically devoted to P3s, so they have a supportive public sector legal and regulatory environment.

The U.S. and Canada are a fairly integrated marketplace, so successful Canadian projects influence the U.S. The Ontario Line in Toronto that I mentioned earlier is a P3 and it’s being closely followed by the U.S. transit community. Another example, the Gordie Howe International Bridge (a Canadian P3 port of entry) influenced the San Diego Association of Governments to explore using a P3 or progressive design-build for a new port of entry on the U.S.-Mexico border. Also, courthouse P3s in Ontario and British Columbia influenced the City of Long Beach to build their new courthouse and justice center as a P3.

Generally governments are looking for the same outcomes — effective project delivery, in a way that reduces risk and results at reasonable cost. The ability to tap innovation is a strong driver in many P3s, as is the ability to consider long-term operations and maintenance as an integral part of project delivery. Cross pollination — promoted by the U.S. Department of Transportation, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, and other entities — can be very effective in spurring new ideas.

Inspiration & Advice

Q. What got you interested in P3s?

A. I advised former Arizona Governor Janet Napolitano on transportation and trade and accompanied her on a trade mission to the U.K. where she was promoting business relationships between the U.K. and Arizona. The U.K. was a very early adopter of P3s and used them extensively for transit and roadways, including additions to the London Underground. The U.K. transportation folks were keen to promote their expertise, hoping U.K. firms might do more work in the United States. The governor was intrigued by their success and asked me to do some research that ultimately led to Arizona passing its own P3 law. I ended up at the Arizona Department of Transportation overseeing the new P3 program — a career path I never expected.

Q. What advice do you have for early-career professionals who want to get involved in P3s?

A. I think this is a delivery method that is well enough established now that it can be viewed as a career path. The necessary skills can be built on the job and some national organizations provide workshops and training such as the American Road & Transportation Builders Association’s P3 Division, which has a young professionals’ track at their conference.

Alternative delivery and P3 projects, perhaps even more than standard design-build and design-bid-build, integrate the technical, finance, management and public engagement components of a project. So whether your interest is in engineering design, project management, infrastructure finance or communications/public engagement, there is real opportunity in these types of projects. And the inter-connected nature of these projects guarantees a chance to learn a lot of new skills, too.

Each Experts Talk interview illuminates a different aspect of transportation infrastructure planning, design and delivery. Check back regularly to discover new insights from the specialized experts and thought leaders behind our award-winning, full service consulting practice