One Water Valuation

This article is part of Stock and Flow, a series offering insights from our economics, statistics and finance team about issues facing water projects.

Public agencies at all levels face difficult choices on water infrastructure, including which projects to implement first, how to fund them given affordability constraints and how to make the case to those who will pay the bills. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, American Water Works Association and others have estimated that upward of $1 trillion may be required over the next decade to repair and replace pipes, equipment, water supply, wastewater and flood control facilities. Elevated risks from climate change and new contaminants only add complexity and costs to decisions. Furthermore, while internal and external stakeholders may justifiably seek to incorporate equity and sustainability into decisions, setting related goals and measuring progress can introduce new uncertainties. While federal and state agencies are increasing support for implementing new and renewed green and grey infrastructure, a significant share of these costs will certainly fall on local communities through water rates and taxes. In this article, we provide insights into the ways that economic analysis can guide investment decisions in such contexts and help make the case for external funding.

Be the first to know

Subscribe to receive our Water Insights

What is the value of One Water?

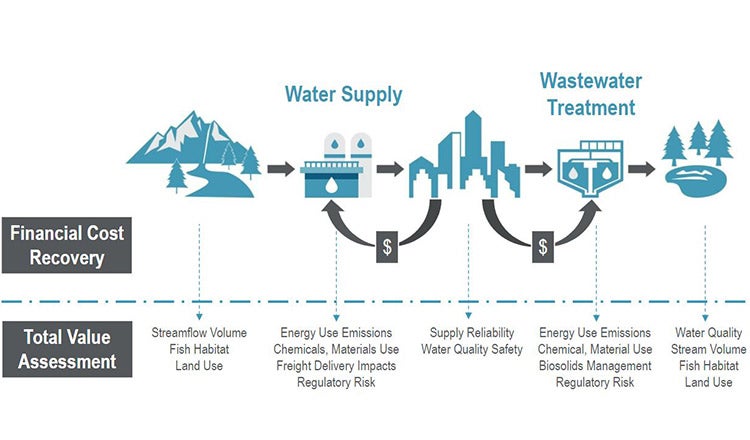

Economic analysis has long contributed to water resource decisions, and for good reason. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers formalized benefit-cost analysis for major water projects in the 1930s. At the time, the National Resources Board saw BCAs as supporting “rational planning” since it could make the best use of evidence to account for “tangible and intangible” benefits and costs, as well as their distribution. Early applications involved BCAs of hydroelectric power and flood control projects, each of which entailed benefits to some people and costs to others. Overall, BCAs were the clearest mechanism to compare project options for identifying the option that generated the greatest societal value. Economic analyses have grown in complexity since then, especially with our understanding of the environment and our impacts on it. An economic analysis of water projects differs from other approaches because it is structured to reveal the total value in decisions. From a day-to-day perspective, developing and managing water resources entails costs and prices. That is, a utility incurs capital and operational costs to develop, clean and distribute water and then collect and treat wastewater. Then, to achieve cost recovery, the utility sets rates, or prices, as part of its budgeting and capital planning process. Utilities manage their spending and rate-setting to achieve cost recovery. Cost recovery is usually a separate activity for water and wastewater utilities, represented in Figure 1 by the money flows from consumers in urban spaces.

One Water Valuation for Infrastructure Planning

The total value of water extends beyond financial cost recovery goals and accounts for externalities in water use. For instance, the energy to deliver water produces greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants, which are not priced into energy costs and thus excluded from water rates. Similarly, neither positive (recreation) nor negative (stream habitat) impacts of water diversion for municipalities are captured in water rates — only the cost of diversions is included. Treatment costs to meet regulatory standards are included in water rates, but not any potential additional impacts downstream. Because the economic value of water accounts for a more complete perspective on the impact of water management decisions to society, it makes an important contribution to decisions whenever externalities are significant. Furthermore, economic valuation methods can be adapted to consider the distribution of costs and benefits to society.

How is the value of water measured?

Evaluations of water resource projects combine scientific and engineering analyses of project impacts with the economic values of those impacts. For instance, engineering analyses can readily estimate the energy sources and loads required for treating and delivering water. Economic analyses determine the value of emissions from energy use associated with impacts on human health and the economy. Hydrologic and biological analyses can determine how diversions from rivers for municipal supplies can affect aquatic life, and economic analyses can estimate the value of those changes in terms of recreational activity and ecosystem services. Today, standard economic methods and data for valuing impacts to water are well established by federal agencies (e.g., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) and in peer-reviewed articles. Challenges can arise in adapting economic research from one location and context to another, but approaches for doing so are now standard practice. In short, economic valuation methods are readily available to evaluate water management decisions alongside engineering. BCA supports strategic planning and investment decisions by determining a total value of water that is comparable across projects, which can differ in scope. Furthermore, where project outcomes can be monetized, BCAs establish a clear assessment of a project’s value-for-money.

How does the value of water contribute to decisions?

At the federal level, USACE and other water resource agencies require BCAs as part of their selection of projects for funding. The EPA also conducts BCAs when evaluating major regulatory standards for water quality. In addition, BCAs were conducted for many of the EPA’s Municipal Integrated Planning Program case studies in which water utilities evaluated project impacts beyond just their cost-effectiveness in achieving a single objective, such as stormwater detention. In such examples, these agencies require BCAs because they are mandated to represent broad societal interests.

Utilities are increasingly considering One Water planning concepts that take a multibenefit, multistakeholder, and systems-thinking approach to identifying priority projects. In practice, a One Water approach aims to look jointly across water, wastewater and stormwater management facilities and operations to identify the best opportunities to meet objectives. One Water planning recognizes that all water has value, including natural and treatment systems, and that decisions should account for economic, environmental, and societal outcomes. Economic analyses are particularly suited to support One Water planning approaches since the valuation of options focuses on outcomes and externalities of water, independent of the entity implementing the change. In addition, economic analyses effectively convert each form of project impact (e.g., kilowatt-hours of energy emissions, concentrations of water quality, volumes of water, etc.) into monetary measure, which in turn enables impacts to be compared and summed on a common basis.

What is our One Water valuation approach?

Our One Water approach is focused on helping clients identify a future of affordable and equitable access to clean water, sustainable water supplies, reliable wastewater services, flood protection and healthy ecosystems to support the continued prosperity of our communities. One Water considers the interconnectivity among all phases of the hydrologic cycle while leveraging partnerships needed to address today’s water challenges and opportunities. With One Water Valuation, each unit of water is evaluated in terms of its financial, environmental and social costs throughout the entire urban water system specific to that community or region. This approach is particularly effective in understanding the benefits of water reuse opportunities since such projects can reduce environmental water demands, which would be unaccounted for in standard life-cycle cost analyses. Moreover, the economic value of water projects can align well with multi-criteria decision analysis approaches and tradeoff analyses.

Where have we applied economic analyses on water projects?

We have applied economic analyses to projects with a wide variety of characteristics. For example, we have developed methods to analyze the value of lost water for irrigation, increased water supplies of water, improved reliability of supplies for municipal users, reduced water contamination in streams, tradeoff analyses between water reuse and desalination projects and impacts of water management on fish populations. One of the most significant long-term engagements has been with the City of Springfield, Missouri, where we have applied BCAs to evaluate a range of projects as part of an integrated water resource management initiative. More recently, economic analyses have been conducted there to evaluate plans for wastewater treatment options that could reduce negative water quality impacts and increase property values. Overall, in these examples and others, economics has played a significant role to support decisions because it reveals projects’ multiple benefits and enables different stakeholders to reach consensus on choosing the projects that achieve the highest societal value.