Elevating the Human Experience in Public Realm Infrastructure

Understanding the Complexities of a Community by Pairing Quantitative Data and Human Needs

As we work together to create a sustainable world for future generations, there are many innovative solutions in the public realm of our cities and communities that reduce waste, energy demand and carbon footprint. But how do these physical infrastructure ideas respond to human needs, and our behavior and mindsets? We must equally consider people as we design, build and evolve our future communities.

I want each of us to consider the questions: What kind of world do we want to live in together? How are we including human experience in our planning for the future?

Around the world, new solutions are emerging that demonstrate the potential to harness renewable energy sources to power our communities. Cities are experimenting with innovative ideas for urban roadway surfaces that reduce stormwater run-off and heat-island effect. These ideas and others hold strong potential to solve physical infrastructure challenges. However, as we work to plan and design infrastructure in our public realm, we must consider quality of life, equity, economic vitality, health, and community connectivity. If we examine human need and define qualitative drivers, we can better the lives of our community members — the people putting our technical engineering, big infrastructure projects to use every day. With projects built around the way we live, we grasp the opportunity to weave together all aspects critical to building a vibrant future.

Communities buy into projects when they see the public good. Listening to the community, and pairing the quantitative and qualitative to tell a story develops a solution that resonates with the community, and not only gains support, but a sense of ownership and pride.

Listen to the Community

Drivers and needs vary from region to region and person to person. Surveys are often used to gather data, but while survey data is helpful, it’s also limited. Questions often aren’t nuanced enough to get to the heart of what matters to residents. A city facing issues of social equity and affordable housing may benefit from new methods of community engagement to frame solutions in terms of health, job and housing access, rather than focusing only on density, roadway design or other physical solutions.

Community engagement methods like public meetings attempt to gather input, inform and educate people about changes coming to their community. But big infrastructure projects, like new roadway systems, new urban redevelopment plans or upgraded stormwater solutions can be challenging to understand — and almost abstract in their scale and influence. It takes more individualized interaction between people to capture and address the complexities of community need.

Community ethnography is a method used often by anthropologists. It's a research method used to understand a population and its need. The inspiration behind that deep research process is what uncovers the community mindset to gain an understanding of why people make the decisions and choices they make.

For example, if a community experienced damaging flooding in specific neighborhoods, addressing their real fears and concerns about future damage to their homes through personas and storytelling may help address deep-seated emotions. We must connect with our community members’ hearts and minds.

This was well done in Denver, for the region’s Denver Mobility Blueprint project. The metro area’s future mobility plans were developed using technical transportation modeling, policy planning and a consideration for the unique mindsets, hopes and fears of residents within the region. The project began with a personal approach that included one-on-one conversations around kitchen tables with a wide variety of people across metro Denver.

Those in-depth conversations didn't just ask, “What type of transportation do you use?” Instead, questions like, “How do you define quality of life?” were paired with exercises to rank quality of life factors. Details covered aspects from health and safety to work, productivity and even heritage — in addition to access to transportation.

To verify that what we learned from the smaller representative sample during face-to-face meetings was representative of a broader audience, we used social media and online technology. The big message we heard from those early conversations was that transportation enables quality of life. You may arrive home after a long day in a better mood because you've had a positive transportation experience through biking, or walking or carpooling. It's not only about how you get from point A to point B. It’s about connecting with your community, and having the flexibility to live your life.

Pair Quantitative Solutions with Qualitative Insights to Tell a Story

When it’s time to present transportation models and new technologies to clients and communities, telling a story around the solutions can be powerful. Instead of presenting spreadsheets and numbers to the community, I’ve found that when we use experiential examples to demonstrate transportation improvements, we find our greatest support.

We followed this approach for the Denver Mobility Blueprint. During community interviews we learned young professionals used smart phone apps to locate social activities in the area, but they felt like visibility around transportation choices in the Denver Metro area was not as intuitive. For this groups, a “smart mobility app” that showed not only personal vehicle driving options, but options for scooters, public transit and Lyft, would improve the transportation experience and encourage use of alternative travel modes. That story around mobility experience was paired with quantitative measures during public presentations, as demonstrated below.

Once community priorities are clearly defined, match technical solutions with human needs to work each element of the broader plan together. One way to do this is to develop personas based on the community groups interviewed. This build contexts around significant project elements and how they’ll impact the community.

To present our solutions we zeroed in on these five personas, which were inspired by the people we met and worked within the Denver Metropolitan area, to show how implementing new technologies and solutions would positively impact relatable people.

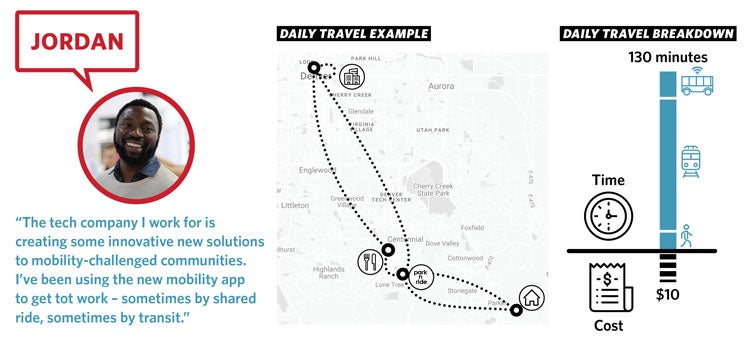

Our “Jordan” persona, for instance, highlights how added mobility options for first and last mile services near a new bus station would enable someone like him to get additional work done on the commute, and how new micro-transit would make it convenient to connect with friends after work.

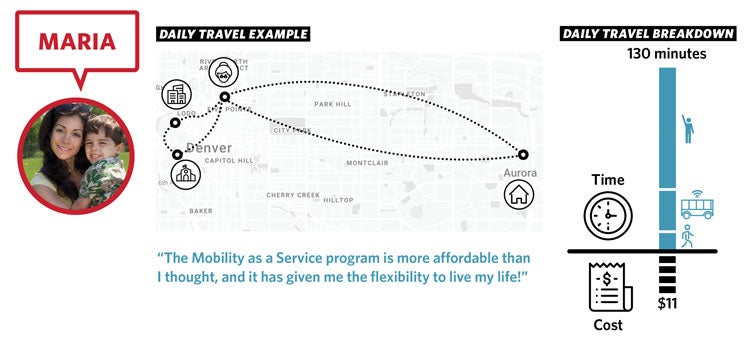

Someone like “Maria” could save time by using micro-transit to get around downtown with more direct options, and spend more time either working (increasing her income) or with family.

Quantifying the benefits of qualitative solutions helps people see the value.

It’s this unique blend of addressing the technical requirements alongside the human needs that makes big changes positive and manageable for the community. While gathering stakeholder input from surveys is beneficial, the shift in approach is best accomplished by connecting large, physical infrastructure changes in our built environment to actual needs identified by community residents.

Changes in a person’s home and community are inevitably emotionally charged. It’s only when we intertwine human needs with mobility solutions that we get to the heart of what our communities need to connect and prosper.